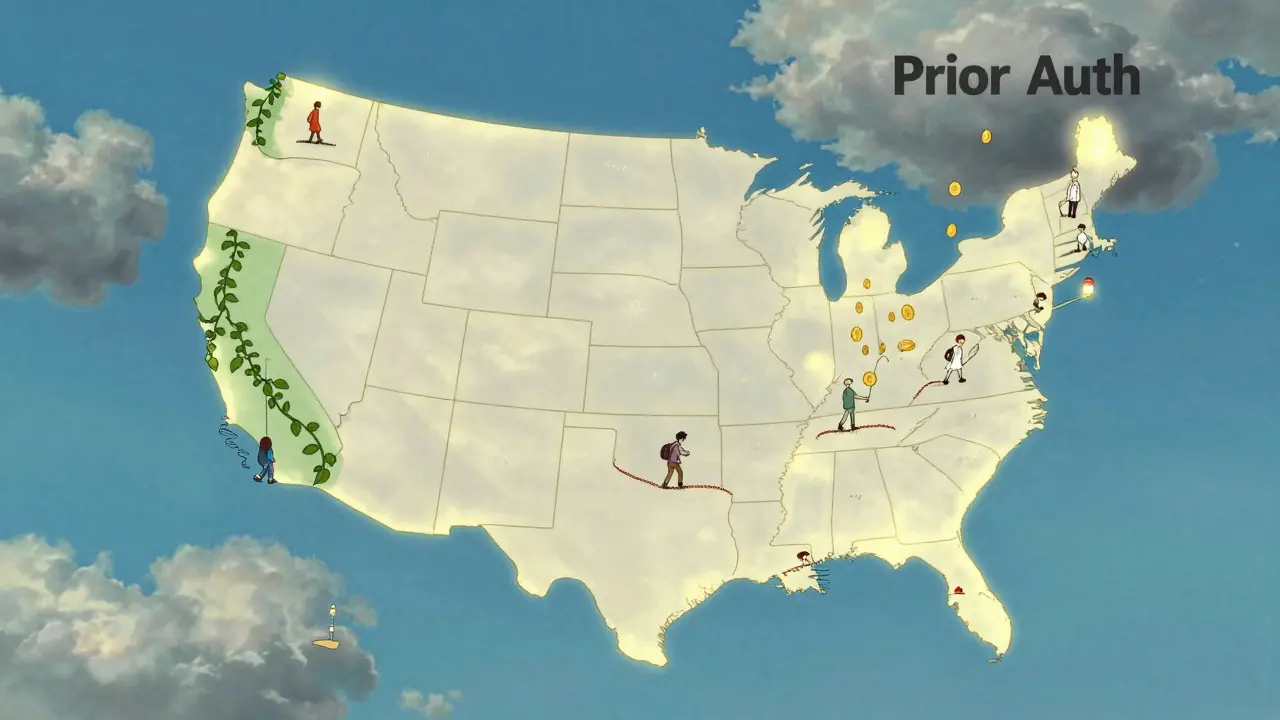

When it comes to getting generic drugs through Medicaid, there’s no one-size-fits-all rule. What’s covered in California might be denied in Texas, and what’s free in New York could cost you $8 in Florida. Even though every state offers prescription drug coverage under Medicaid, the Medicaid generic coverage rules vary wildly - from who can switch generics to how long you wait for approval. If you’re on Medicaid and rely on generic medications, understanding your state’s specific rules isn’t just helpful - it’s essential to avoid delays, denials, or unexpected bills.

Every State Covers Generics - But How?

All 50 states and Washington, D.C., cover outpatient prescription drugs for Medicaid enrollees. That’s not optional - it’s how the program works. But federal law only sets the floor, not the ceiling. States have wide freedom to design their own formularies, set copays, and decide when a generic drug can be substituted for a brand-name version. The result? A patchwork system that can be confusing even for doctors. At least 41 states require pharmacists to automatically substitute a generic drug when it’s available and approved as therapeutically equivalent by the FDA. In Colorado, for example, the law says a pharmacist must switch to the generic unless the prescriber writes "dispense as written" or the brand version is actually cheaper. Other states, like California, take a lighter touch - they encourage substitution but don’t force it. This matters because if your pharmacist can’t swap your brand-name pill for the generic without calling your doctor first, you could be stuck waiting days for a refill.How Much Do You Pay? Copays Vary by State

You might think generics are always cheap - and for Medicaid, they often are. But you’re not always getting them for free. States can charge copays for non-preferred generic drugs, and those fees can range from $0 to $8 per prescription. The federal limit for most low-income Medicaid beneficiaries is $8, but many states set it lower or waive it entirely. In states like New York and Massachusetts, most generic drugs have no copay for beneficiaries earning under 150% of the federal poverty level. In contrast, Texas and Georgia charge $5 for non-preferred generics. And if you’re on a preferred drug list (PDL), you might pay nothing. But if your drug isn’t on that list, you’re looking at a higher copay - or worse, a prior authorization hurdle.Formularies: The Secret List That Controls Your Access

Every state has a formulary - a list of drugs that Medicaid will pay for. These lists are divided into tiers. Tier 1 is usually generic drugs. Tier 2 is brand-name drugs. Tier 3? Often specialty drugs that cost hundreds or thousands of dollars. But here’s the catch: just because a drug is generic doesn’t mean it’s automatically on your state’s Tier 1 list. States pick which generics they’ll cover based on cost, clinical guidelines, and negotiations with drug manufacturers. CVS Caremark, OptumRx, and Express Scripts manage pharmacy benefits for Medicaid in 37 states, and each has its own preferred drug list. So your generic metformin might be covered in Ohio but not in Alabama - even if they’re the same pill. Some states use open formularies - meaning almost all FDA-approved generics are covered. Others use closed or restricted formularies, where you need approval just to get a common generic like lisinopril or atorvastatin. In states with tight controls, you might need to try two or three other generics first before your insurer will cover the one your doctor prescribed. This is called step therapy, and it’s used in at least 32 states.Prior Authorization: The Hidden Roadblock

Prior authorization is when your doctor has to call or submit paperwork to prove you need a specific drug before Medicaid will pay for it. For brand-name drugs, this is common. But increasingly, it’s happening with generics too. In Colorado, for instance, you need prior authorization for almost any drug not on the Preferred Drug List - even if it’s a generic. And the requirements aren’t simple. For certain gastrointestinal drugs, you might have to prove you’ve tried three different preferred NSAIDs and three proton pump inhibitors over six months before they’ll approve your prescription. Other states, like California, rarely require prior authorization for generics. But in states with stricter rules, the approval process can take 24 to 72 hours. And if your doctor’s office doesn’t have the right paperwork or the right contact at the PBM, your refill gets delayed. The American Medical Association found that primary care doctors spend an average of 15.3 minutes per patient just dealing with prior authorization requests - that’s over 8,000 hours of administrative work per year across a typical practice.

Therapeutic Substitution and Pharmacist Power

In 17 states, pharmacists aren’t just allowed to swap generics - they’re encouraged to do so if the price difference is over $10. This is called therapeutic interchange. It means your pharmacist can switch your generic amlodipine to a cheaper version without asking your doctor - as long as it’s considered clinically equivalent. But here’s where it gets messy: 28 states require the pharmacist to notify your doctor when they make the switch. Twelve states don’t. If you’re not told, you might show up for your next appointment and your doctor won’t know you’re on a different version of the same drug. That’s risky if you have conditions like epilepsy, heart disease, or mental health disorders where small differences in absorption can cause side effects. The FDA rates generic drugs for therapeutic equivalence using the Orange Book. States like Florida and Illinois use that rating directly in their substitution laws. But not all states do. Some rely on their own internal lists, which can be outdated or inconsistent.Why Some Generics Are Still Expensive - Even on Medicaid

You’d think generics are always cheap. But that’s not always true. Between 2019 and 2024, the price of some critical generic drugs - like insulin, certain antibiotics, and seizure medications - rose sharply, even as overall drug prices fell. Medicaid programs didn’t get the usual rebates on these because of loopholes in the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program. The program, created in 1990, requires drug makers to pay rebates to states in exchange for having their drugs covered. But if a generic drug’s price increases faster than inflation, the rebate doesn’t always keep up. In 2025, Congress is considering a bill that would exclude most generics from inflation-based rebates. If it passes, states could lose an estimated $1.2 billion in annual rebate revenue. That could mean tighter formularies, higher copays, or even drug shortages. Meanwhile, supply chain issues are making some generics hard to find. The FDA’s 2024 drug shortage list included 17 generic medications covered by Medicaid - including drugs used for heart failure, depression, and infection. When those run out, patients are forced onto more expensive alternatives - or go without.What’s Changing in 2025 and Beyond

A major shift is coming. In December 2024, the federal government proposed a rule requiring all Medicaid programs to cover anti-obesity medications - including newer generics like semaglutide. If approved, this would affect nearly 5 million people with obesity-related conditions. It’s the first time since the Affordable Care Act that a new drug class is being mandated. Also, starting in 2025, people who qualify for both Medicaid and Medicare can change their Part D drug plans once a month. That’s a big deal. Previously, you had to wait until the fall. Now, if your Medicaid formulary changes or your drug gets pulled, you can switch your Medicare plan faster to keep your meds covered. States are also testing new models. Michigan, for example, cut diabetes medication costs by 11.2% by using value-based purchasing - paying more for drugs that keep people out of the hospital. Only nine states have tried this so far, but interest is growing.What You Can Do

If you’re on Medicaid and take generics:- Check your state’s Preferred Drug List (PDL). Most state Medicaid websites have it online.

- Ask your pharmacist if your generic is on the preferred list - and if not, why.

- If your drug requires prior authorization, ask your doctor’s office to submit it early. Don’t wait until your prescription runs out.

- Request a therapeutic substitution if your drug is expensive. Your pharmacist might be able to switch you to a cheaper, equally effective version.

- Keep a list of all your medications and the doses you’re on. If your pharmacist switches your generic, you’ll know what changed.

State-by-State Quick Reference

Here’s a snapshot of how a few states handle generic coverage:| State | Automatic Generic Substitution? | Max Copay for Non-Preferred Generic | Prior Auth for Generics? | Step Therapy Required? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| California | Yes, encouraged | $0 | Rarely | No |

| Colorado | Mandatory (with exceptions) | $5 | Yes, for non-preferred drugs | Yes, for GI and pain meds |

| Texas | Yes | $8 | Yes, for certain generics | Yes, for antidepressants |

| New York | Mandatory | $0 | No | No |

| Florida | Mandatory | $4 | Yes, for high-cost generics | Yes, for statins |

| Massachusetts | Mandatory | $0 | Minimal | Yes, for some psychiatric drugs |

These differences aren’t random. They reflect each state’s budget, political priorities, and how aggressively they’re trying to control drug costs. But for the people who rely on these drugs, the inconsistency creates real barriers to care.

Bottom Line

Medicaid generic coverage is one of the most effective ways to keep healthcare affordable - but only if you know the rules. The system is designed to save money, but it often saves it at the cost of convenience, clarity, and sometimes, health. The best defense? Know your state’s formulary, ask questions, and don’t assume your generic will be covered the same way everywhere.Are all generic drugs covered by Medicaid in every state?

No. While every state covers some generic drugs, not all generics are included on each state’s preferred drug list. States pick which generics to cover based on cost, clinical guidelines, and negotiations with drug manufacturers. Some states have open formularies that cover nearly all FDA-approved generics, while others restrict coverage to only the cheapest or most clinically preferred versions.

Can my pharmacist switch my brand-name drug to a generic without my doctor’s approval?

In 41 states, yes - if the generic is FDA-rated as therapeutically equivalent and your doctor hasn’t written "dispense as written." In some states like Colorado, pharmacists are required to substitute unless there’s a specific exception. In others, substitution is allowed but not required. Always check your state’s pharmacy laws and ask your pharmacist what they can do without calling your doctor.

Why do I have to try other drugs before Medicaid covers my generic?

This is called step therapy, and it’s used in at least 32 states to control costs. Medicaid requires you to try cheaper, preferred drugs first before covering a more expensive one - even if it’s a generic. For example, you might need to try three different generic pain relievers before Medicaid will cover your prescribed one. This is meant to save money, but it can delay treatment and lead to frustration.

How do I find out what drugs my state’s Medicaid program covers?

Visit your state’s Medicaid website and search for "Preferred Drug List" or "Formulary." Most states publish these lists online, often with searchable databases. You can also call your Medicaid office or ask your pharmacist to check the formulary for you. Some states, like Massachusetts and New York, offer apps or online tools to look up coverage.

What should I do if my generic drug is denied by Medicaid?

First, ask your doctor to file a prior authorization request - they can explain why the drug is medically necessary. If that’s denied, you can appeal the decision. Most states have a formal appeals process, and you have the right to request an expedited review if your health is at risk. Keep copies of all paperwork, and consider asking a patient advocate or legal aid group for help if you’re stuck.

why do states even bother with all this mess. just cover the damn generics. i got my script denied because some bureaucrat in texas decided lisinopril isnt preferred anymore. like i care about your formulary. i just need to not die.

no cap.

my pharmacist had to call my doctor 3 times. 3 times. for a 5 cent pill.

Let me get this straight: 41 states mandate generic substitution, yet 17 allow pharmacists to perform therapeutic interchange without notifying the prescriber-and in 12, they don’t even have to tell you. This isn’t healthcare policy. It’s a regulatory Rube Goldberg machine designed by people who’ve never taken a pill in their life.

And yet, the FDA’s Orange Book is the gold standard, but half the states use internal lists that haven’t been updated since 2018. That’s not cost control. That’s negligence dressed up as efficiency.

Yo, just wanted to say this post was super helpful. I’m in Georgia and didn’t realize my $5 copay was actually the max. Thought I was getting ripped off. Turns out I’m lucky. Had no idea about step therapy for antidepressants either. Just saved me a trip to the pharmacy this week. Thanks for breaking it down.

Also, if you’re on Medicaid, always ask your pharmacist if they can swap your generic for a cheaper one. They know the formulary better than your doctor sometimes.

Oh, so we’ve reduced human health to a spreadsheet. A spreadsheet managed by CVS Caremark, a corporation whose sole mission is to extract maximum profit from the suffering of the indigent.

And we call this ‘affordable care.’

Let me be clear: when your life depends on a pill, and your state’s Medicaid formulary treats it like a luxury item, you’re not in a healthcare system. You’re in a dystopian auction house where the highest bidder wins survival.

And the FDA? The Orange Book? A paper-thin veil over a system that lets a $0.02 generic become a $2.00 nightmare because some lobbyist whispered in the right ear.

This isn’t policy. It’s moral decay with a side of bureaucracy.

Let me be unequivocal: the current Medicaid generic coverage framework is a systemic failure that disproportionately impacts low-income, chronically ill populations. The variation in copay structures, prior authorization requirements, and therapeutic substitution protocols is not merely inconsistent-it is actively harmful.

When a patient with hypertension must undergo step therapy to access atorvastatin, and the delay results in an avoidable hospitalization, the cost to the system exceeds the savings. The AMA’s data on 15.3 minutes per prior authorization is not a statistic-it’s a moral indictment.

States must adopt uniform, transparent formularies aligned with FDA therapeutic equivalence ratings. No exceptions. No loopholes. No bureaucratic theater. Patients deserve predictability, not a labyrinth.

you people act like this is a surprise. every state is run by a bunch of corrupt politicians who take pharma bribes and then pretend they care about poor people. you think florida charges $4 because they’re nice? no. they’re charging $4 because they got a kickback from the PBM to make lisinopril ‘non-preferred’ so they can push a more expensive generic that’s owned by their cousin’s friend’s shell company.

stop acting like this is about healthcare. it’s about money. always has been. always will be.

bro. i just found out my state’s formulary changes every 3 months and no one tells you. i’ve been on the same meds for 2 years and suddenly they’re not covered. i had to go to 3 different pharmacies before one knew what was going on.

also. why do i need to try 5 other antidepressants before they let me take the one that works? i’m not a lab rat. i’m a person. this is wild.

someone needs to start a petition. or a podcast. or both. this is insane.

As a care coordinator for Medicaid enrollees, I see the fallout daily. The fragmentation of formularies creates cascading clinical risks: medication non-adherence, therapeutic duplication, adverse drug events. When a pharmacist switches a patient from one generic amlodipine to another without documentation, and the patient’s cardiologist is unaware, you’re not just changing a pill-you’re altering pharmacokinetics in a population with high polypharmacy burden.

What’s needed isn’t just transparency-it’s interoperability. A national, real-time formulary feed synced to EHRs. No more manual checks. No more calls to PBMs. Just a seamless, patient-centered system. We have the tech. We lack the will.

It’s not rocket science. If you’re on Medicaid and you’re asking why your generic isn’t covered, you didn’t do your homework. The formularies are publicly available. The PDLs are searchable. The prior auth requirements are posted on state websites. This isn’t a conspiracy-it’s a responsibility. You want coverage? You need to be proactive. Stop blaming the system. Start reading the damn PDFs.