DRESS Syndrome Risk Calculator

This tool helps assess the probability of DRESS syndrome using the RegiSCAR scoring system. Enter your symptoms and lab values to calculate your risk score.

Your DRESS Risk Score

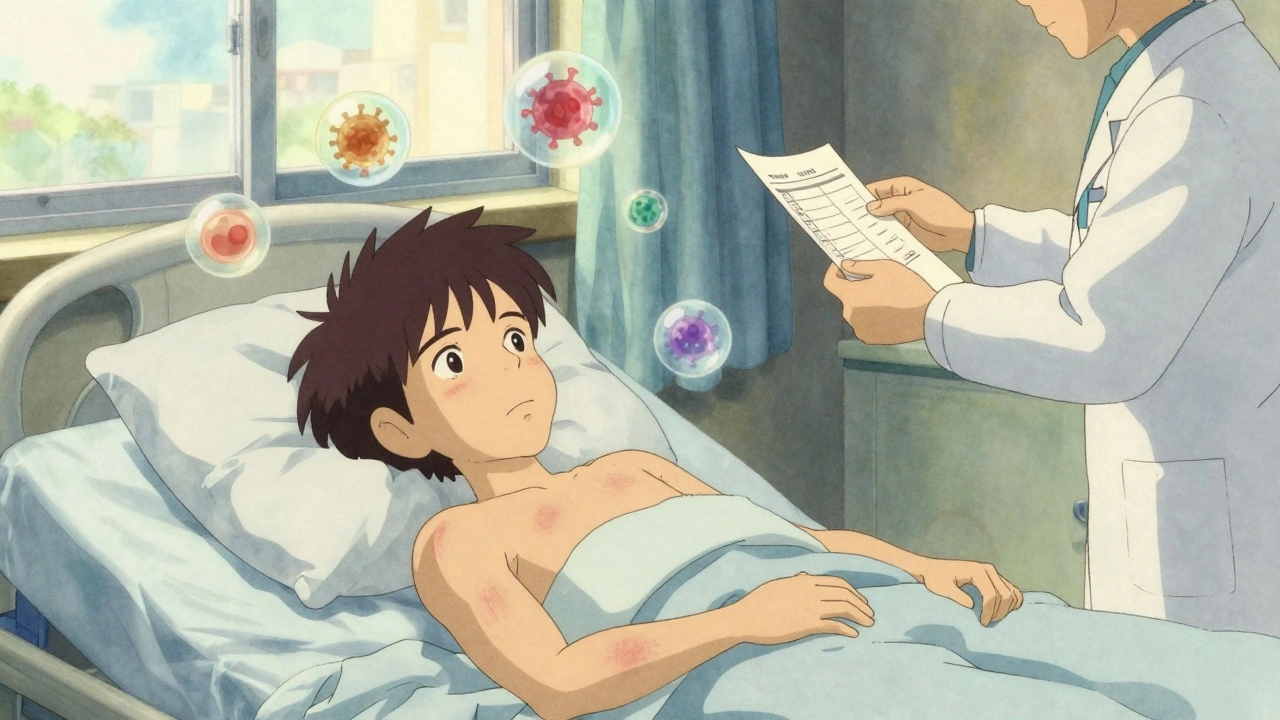

It’s been six weeks since you started that new medication. You’ve got a rash, a fever that won’t quit, and your skin feels like it’s on fire. Your doctor says it’s a virus. Then your liver enzymes spike. Your lymph nodes swell. Still no answers. By the time you’re admitted to the hospital, your eosinophil count is over 4,000. That’s when someone finally says it: DRESS.

DRESS - Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms - isn’t just another rash. It’s a full-body alarm. A rare but deadly response to certain medications that can turn a simple prescription into a life-or-death situation. Unlike a typical allergic reaction that shows up in hours, DRESS creeps in. It hides. And by the time it’s recognized, organs are already under attack.

How DRESS Starts - and Why It’s So Hard to Spot

DRESS doesn’t hit fast. It waits. Most cases appear 2 to 8 weeks after taking the drug. That delay is why it’s so often mistaken for the flu, mononucleosis, or a viral skin infection. The rash starts as red, flat spots on the face or upper chest. Within days, it spreads. Up to 90% of your body may be covered. Your face puffs up. Your lips crack. You’re running a fever above 38.5°C - and it won’t break.

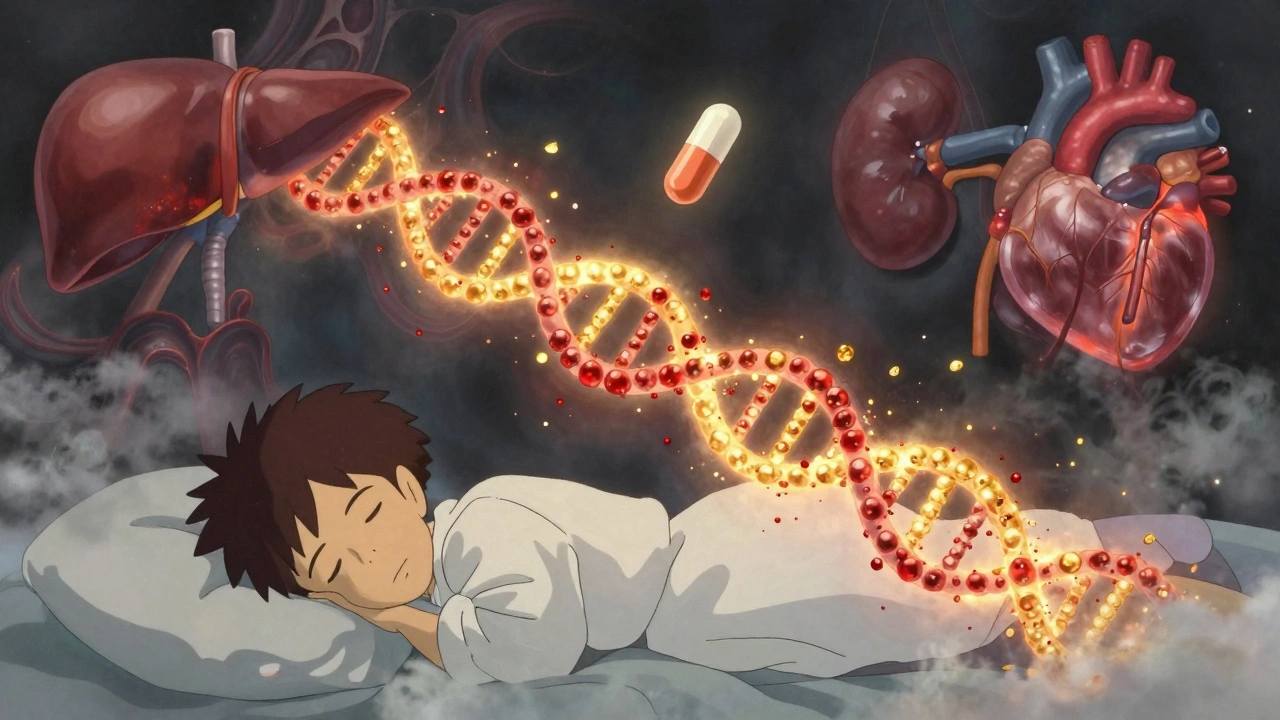

But the rash is just the tip. The real danger is inside. In 90% of cases, internal organs get involved. The liver takes the hardest hit - 78% of patients show ALT levels over 300 IU/L, sometimes over 1,000. Kidneys, lungs, heart, even the pancreas can flare up. Blood tests reveal eosinophils - a type of white blood cell - skyrocketing past 1,500 cells/μL. Atypical lymphocytes show up too. These aren’t random findings. They’re the fingerprints of DRESS.

And here’s what makes it even trickier: viruses wake up. In 60 to 80% of cases, HHV-6 - a herpes virus most people carry silently - reactivates. That’s not a coincidence. It’s part of the mechanism. The drug triggers an immune chain reaction, and the virus gets dragged into the chaos. That’s why some patients test positive for “mono” but don’t have Epstein-Barr. It’s HHV-6, activated by the medication.

What Medications Trigger DRESS?

Not every drug causes DRESS. But some are well-known culprits. Allopurinol, used for gout, is the #1 offender - responsible for nearly 30% of cases. If you have the HLA-B*58:01 gene, your risk jumps dramatically. Carbamazepine and phenytoin, both antiseizure drugs, are next. About 24% of cases link to these. Antibiotics like vancomycin and sulfonamides make up another 20%. Even some antivirals and NSAIDs have been tied to it.

But it’s not just the drug. It’s your genes. HLA-B*58:01 is a genetic marker that tells your immune system to overreact to allopurinol. HLA-A*31:01 does the same with carbamazepine. In Taiwan, doctors screen for these genes before prescribing. The result? An 80% drop in DRESS cases. In the U.S., that screening isn’t routine. That’s why more people here still get hit.

DRESS vs. Other Severe Drug Reactions

It’s easy to confuse DRESS with Stevens-Johnson Syndrome (SJS) or Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis (TEN). But they’re different beasts. SJS/TEN come on fast - within 1 to 2 weeks. The skin blisters and peels off. Mucous membranes in your mouth, eyes, and genitals are destroyed. Mortality? Up to 35%.

DRESS? Slower. Less skin sloughing. More internal chaos. You don’t lose your skin - but your liver, kidneys, or heart might fail. Eosinophilia? That’s DRESS’s signature. SJS/TEN don’t show it. Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis (AGEP) has pustules - tiny white bumps - and shows up in days, not weeks. DRESS doesn’t have pustules. It has fever, swelling, and organ damage.

The RegiSCAR scoring system is the gold standard for diagnosis. It looks at timing, rash type, fever, organ involvement, blood results, and viral reactivation. A score of 4 or higher? High probability of DRESS. That’s how experts confirm it - not just by symptoms, but by the pattern.

Why Diagnosis Is Often Delayed - and What That Costs

Patients report going to the ER two, three, even five times before someone says, “This might be DRESS.” A 2022 survey from the DRESS Syndrome Foundation found the average delay was nearly three weeks. Why? Most doctors have never seen a case. One study found only 38% of primary care physicians could correctly identify DRESS criteria. In community hospitals, protocols are rare. In academic centers, they’re common.

The cost of delay isn’t just time - it’s survival. For every day treatment is postponed, the risk of permanent organ damage climbs. One patient developed irreversible kidney failure after 22 days of undiagnosed carbamazepine use. Another needed a liver transplant. The mortality rate? Around 10%. That’s higher than AGEP, lower than SJS/TEN - but still devastating.

And the financial toll? In 2022, the average hospital stay for DRESS cost $28,500 in the U.S. That’s not counting follow-up care, long-term steroid use, or lost wages. Insurance doesn’t cover the hidden costs - the months of fatigue, the autoimmune flare-ups that linger for years.

How DRESS Is Treated - And What Works

Step one: Stop the drug. Immediately. No exceptions. Even if you think it’s helping your gout or seizures, it’s not worth your life. The second step: hospitalization. Most experts agree - if DRESS is suspected, you need to be in the hospital. Not just for monitoring, but for rapid intervention.

Corticosteroids are the main treatment. Prednisone, usually started at 0.5 to 1 mg per kg of body weight. It’s not perfect - there are no big randomized trials proving it saves lives - but in real-world cases, 60 to 70% of patients improve within 72 hours if treatment starts early. The trick? Tapering slowly. Too fast, and the inflammation comes roaring back. Most patients stay on steroids for 3 to 6 months, reducing by 5 to 10 mg every week.

For severe cases - liver enzymes over 1,000, creatinine above 2.0, or breathing trouble - ICU-level care is needed. Some hospitals use IVIG (intravenous immunoglobulin) or mycophenolate as steroid-sparing options. These are still experimental, but early results from Vanderbilt’s 2023 trial look promising.

And yes - you need viral testing. HHV-6, EBV, CMV, hepatitis. If HHV-6 is active, antivirals like valganciclovir are sometimes added, though evidence is mixed. The goal isn’t to kill the virus - it’s to calm the immune storm it’s fueling.

What Happens After You Survive

Recovery doesn’t end when the rash fades. Many patients face long-term issues. Autoimmune thyroid disease. Chronic fatigue. Kidney scarring. Liver fibrosis. One woman, Sarah Johnson, recovered from vancomycin-induced DRESS after 8 weeks in the hospital and 6 months of tapering prednisone. She returned to work as a nurse - but still gets monthly blood work. She knows the signs. She’s lucky.

Others aren’t. A 2022 study in the Journal of Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery followed 37 DRESS survivors. One-third developed new autoimmune conditions within two years. That’s why follow-up isn’t optional - it’s essential. You need to see a dermatologist, an immunologist, and a primary care doctor who understands this isn’t just “a bad reaction.” It’s a lifelong risk factor.

What’s Changing - And What’s Coming

Good news: We’re getting better at stopping DRESS before it starts. In March 2023, the FDA approved the first point-of-care test for HLA-B*58:01. It gives results in under an hour. That means, before you even get your first allopurinol pill, your doctor can check your genes. No guesswork. No waiting.

The DRESS Syndrome Foundation launched a global registry in September 2023. Over 47 centers in 18 countries are now tracking cases. That data will help identify new triggers - especially as more cancer immunotherapies are used. Early signs suggest checkpoint inhibitors can cause DRESS too.

And research is moving fast. Scientists are hunting for biomarkers - blood proteins or gene signals - that predict who’ll develop chronic complications. If we can spot that early, we can intervene before the damage sticks.

Within five years, experts predict pre-prescription HLA screening will be standard for all high-risk drugs. That could cut DRESS cases by 60 to 70%. But until then, awareness is your best defense.

What You Should Do Now

If you’re taking allopurinol, carbamazepine, phenytoin, or certain antibiotics - and you’ve had a fever and rash for over two weeks - don’t wait. Get your blood tested. Ask for a complete blood count with differential. Check your liver enzymes. Ask: Could this be DRESS?

If you’re a patient, keep a list of every medication you’ve taken in the last 60 days. Bring it to every appointment. If you’ve had DRESS before, never take the same drug again - or anything chemically similar. Even a small dose can trigger a worse reaction.

If you’re a doctor - learn the RegiSCAR criteria. Use the mobile app. Don’t dismiss a rash that shows up late. Don’t assume it’s viral. DRESS doesn’t care if you’ve never seen it. It’ll still happen.

It’s not common. But when it hits - it hits hard. And the only thing more dangerous than getting DRESS is not knowing it’s there.

Been on allopurinol for three years no issues but this post scared the hell outta me. My cousin had something like this and ended up in ICU for a month. Never thought meds could do that. Just goes to show you never really know what your body’s gonna do.

There’s a deeper truth here - medicine treats symptoms, not systems. DRESS isn’t an accident. It’s the body screaming because we’ve ignored the connection between genes, environment, and pharmaceuticals. We treat drugs like candy. We need to treat biology like a sacred contract.

bro i took carbamazepine for like 2 weeks and got a tiny rash… thought it was just my laundry detergent 😅

Interesting.

I’ve been following this topic since my sister had DRESS from sulfamethoxazole. It took five ER visits and three different doctors before someone finally connected the dots. The delay isn’t just frustrating - it’s deadly. And it’s not just about the drug. It’s about how little training most doctors get on delayed hypersensitivity. Medical schools barely mention it. We’re relying on luck when we should be relying on protocols. We need mandatory continuing education on drug reactions, especially for primary care. And we need better tools - not just HLA testing, but real-time alerts in EHRs. If your patient is on allopurinol and has a fever and elevated LFTs, the system should scream, not whisper.

I had this. Took me 17 days. They thought it was shingles. Then it was lupus. Then they said I was just stressed. My mom cried when they finally said DRESS. I’m still on steroids. My liver’s fine now but I get tired just walking to the mailbox. You think you’re fine after the rash goes away. You’re not. It never really leaves you.

Everyone’s acting like this is new. Newsflash - this has been documented since the 80s. The real problem? People don’t read the damn insert. And now everyone wants a genetic test like it’s a magic shield. You think HLA screening will stop all cases? What about the 40% of DRESS cases that aren’t linked to known alleles? You’re just trading one ignorance for another.

Y’all are missing the point. This isn’t about drugs. It’s about trust. We’ve been trained to believe pills are safe. But the system’s rigged. Pharma doesn’t want you to know the truth. They push these meds hard, then vanish when things go south. DRESS isn’t rare - it’s hidden. And the real victims? The ones who can’t afford to fight the system.

My dad’s a pharmacist. He told me once: ‘If your rash shows up after three weeks, it’s not a virus - it’s your immune system doing a backflip.’ I never forgot that. This post? It’s the kind of thing every single person on meds should read. Not because it’s scary - because it’s real. And if you’re on allopurinol or carbamazepine? Print this out. Show your doctor. Don’t wait for them to know what it is. Be the one who asks first.

It is an epistemological paradox that a therapeutic agent, designed to ameliorate physiological dysfunction, may simultaneously induce a systemic catastrophe through immunological misrecognition. The ontological fragility of pharmacological intervention remains inadequately addressed within contemporary clinical paradigms.

Let me tell you - I’ve seen this in a hospital in Delhi. A 24-year-old girl. Vancomycin. Three months in ICU. Her parents sold their land to pay for IVIG. And you know what? The doctor who treated her? He didn’t even know what DRESS was until she coded. This isn’t just an American problem. It’s a global failure of medical education. And the worst part? Nobody talks about it. Because if they did… people might stop taking pills.

Just got my HLA-B*58:01 test back last week - negative 😌 I’m still taking allopurinol but now I feel like I’ve got a cheat code. Thanks for the heads up, OP. This stuff matters.

So we’re supposed to panic because some guy wrote a 10,000-word essay about a condition that affects 1 in 10,000 people? Congrats. You’ve turned a rare side effect into a viral fear campaign. Next you’ll be telling us to avoid aspirin because someone once got a rash. Chill. Your meds aren’t trying to kill you. Your anxiety is.