If you’ve ever looked in the mirror and noticed a pink, fleshy wedge growing from the white of your eye toward your pupil, you’re not alone. This isn’t a scratch, an infection, or a weird mole-it’s pterygium, commonly called ‘Surfer’s Eye.’ And while it sounds harmless, it can quietly steal your vision if left unchecked. The truth? It’s not rare. Around 12% of men over 60 in Australia have it. In places near the equator, that number jumps even higher. And it’s not just surfers. Anyone who spends time outdoors-gardeners, construction workers, cyclists, even commuters walking to work-can develop it. The culprit? Sunlight. Not just any sunlight, but ultraviolet (UV) radiation. This isn’t a myth. It’s science. And the good news? You can stop it in its tracks-or fix it-if you know how.

What Exactly Is a Pterygium?

A pterygium is a growth of the conjunctiva-the clear, thin membrane covering the white part of your eye-that creeps onto the cornea, the clear dome in front of your iris. It starts small, often looking like a harmless red spot near the nose side of your eye. Over time, it can grow into a triangular flap, sometimes reaching all the way to your pupil. It’s not cancer. It won’t spread inside your body. But it can mess with your vision.

When it grows over the cornea, it distorts the shape of your eye’s surface. That’s when blurry vision, astigmatism, or even double vision can start. You might also feel grit, burning, or constant irritation-like sand is stuck in your eye. In advanced cases, wearing contact lenses becomes impossible. About 60% of people with pterygium have it in both eyes, especially if they live near the equator or spend a lot of time outside without eye protection.

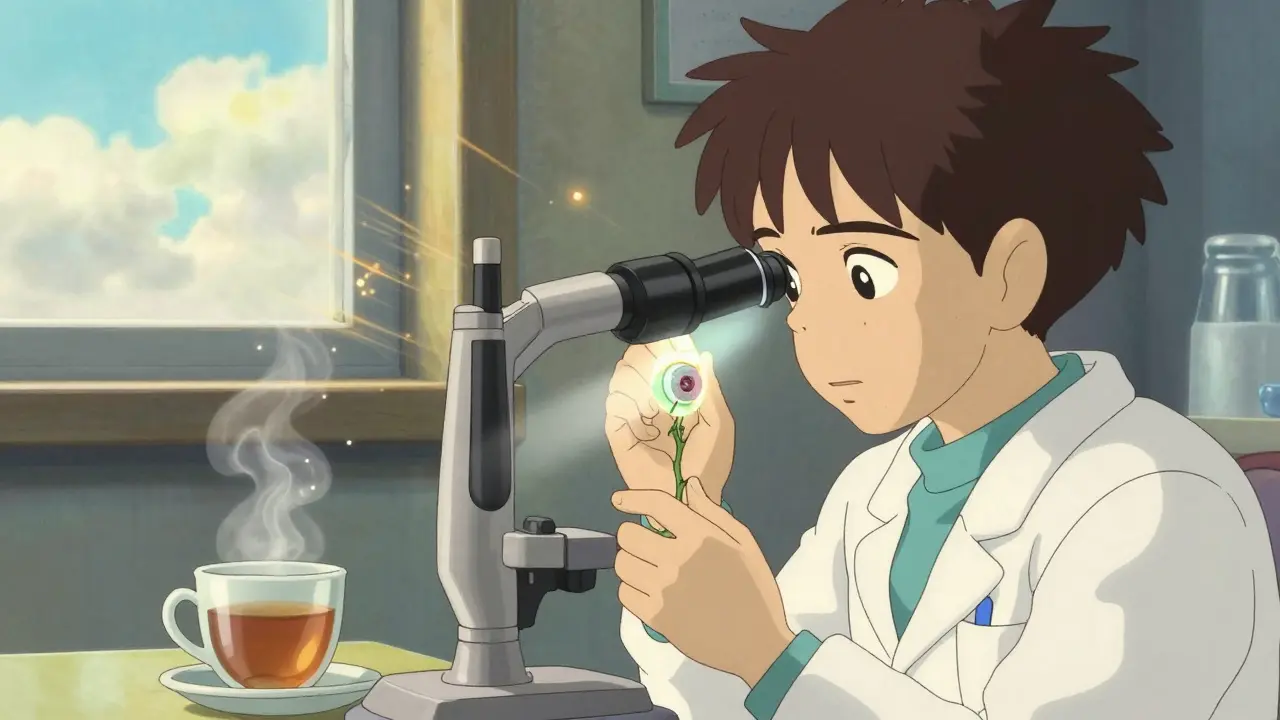

Doctors diagnose it with a simple slit-lamp exam-a bright, magnified light that lets them see exactly how far the growth has traveled. No blood tests. No scans. Just a look. That’s why so many cases go unnoticed until they’re already bothering you.

Why the Sun Is the Main Culprit

UV radiation is the number one cause. Not just UVB-the kind that gives you sunburn-but UVA too, which penetrates deeper. Studies show people living within 30 degrees of the equator have 2.3 times higher risk of developing pterygium than those in northern or southern latitudes. That’s why Australia has the highest rates globally, with 23% of adults over 40 affected.

Research from the University of Melbourne found that if your total UV exposure hits 15,000 joules per square meter over your lifetime, your risk jumps by 78%. That’s roughly the amount you’d get from 20 years of daily outdoor work without sunglasses. And it’s cumulative. Every hour adds up.

It’s not just about being outside-it’s about being unprotected. A 2021 study showed that outdoor workers in tropical areas have a 30% chance of developing pterygium, while those who wear proper UV-blocking sunglasses cut that risk nearly in half. Even on cloudy days, up to 80% of UV rays still reach your eyes. Snow, water, and sand reflect UV light, making exposure worse. That’s why skiers, fishermen, and beachgoers are at high risk.

Genetics might play a small role-some families seem more prone to it-but environmental exposure accounts for 85% of cases. If your dad had it and you’re out in the sun all day, you’re not just inheriting a trait-you’re inheriting a risk that’s still under your control.

How Fast Does It Grow?

There’s no set timeline. Some pterygia stay tiny for years. Others creep forward at 0.5 to 2 millimeters per year. That might not sound like much, but if it grows just 1 millimeter over your cornea, it can already cause noticeable blurriness. The growth rate depends on how much UV you’re exposed to. If you keep going without protection, it will likely keep growing. If you start wearing sunglasses and a hat every day, many cases stop progressing entirely.

One Reddit user, ‘OutdoorPhotog,’ shared that after switching to UV-blocking sunglasses, his pterygium didn’t grow at all over two annual check-ups. That’s not luck. That’s prevention working.

What’s the Difference Between Pterygium and Pinguecula?

People often confuse the two. A pinguecula is a yellowish bump on the white of the eye, usually near the nose. It’s made of protein, fat, and calcium deposits. It stays on the conjunctiva and never reaches the cornea. That’s the key difference. Once it crosses onto the cornea, it’s officially a pterygium.

Pinguecula is way more common-up to 70% of outdoor workers in tropical zones have it. But it rarely affects vision. Pterygium, though less common, is the one that threatens sight. Think of pinguecula as a warning sign. If you have one, you’re already at higher risk for pterygium. Protect your eyes now, before it moves.

Surgical Options: When and How It’s Done

If your pterygium is small and not bothering you, you don’t need surgery. Eye drops, artificial tears, and sunglasses are enough. But if it’s growing toward your pupil, causing blurry vision, or making contact lenses unbearable, surgery becomes the next step.

There are three main surgical approaches:

- Simple excision: The growth is cut out. Cheap and quick. But without extra treatment, it comes back in 30-40% of cases. That’s why it’s rarely used alone anymore.

- Conjunctival autograft: The surgeon removes the pterygium and replaces it with a small piece of healthy conjunctiva taken from under your eyelid. This is now the gold standard. Recurrence rates drop to just 8.7%.

- Mitomycin C or amniotic membrane: Mitomycin C is a medication applied during surgery to stop abnormal cells from regrowing. It cuts recurrence to 5-10%. Amniotic membrane-taken from donated placental tissue-is used for recurrent cases and has shown 92% success in preventing regrowth, according to 2023 European guidelines.

Surgery usually takes less than 40 minutes. You’re awake but numb. Most people go home the same day. Recovery? You’ll have redness, watering, and mild discomfort for 2-3 weeks. Steroid eye drops are needed for up to six weeks to reduce swelling and prevent recurrence. One patient on RealSelf said the drops were harder than the surgery itself.

What Works Best? The Data Says This

Let’s compare the most common surgical methods:

| Method | Recurrence Rate | Recovery Time | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simple Excision | 30-40% | 1-2 weeks | Low-risk, non-growing cases (rarely recommended) |

| Conjunctival Autograft | 8.7% | 2-3 weeks | First-time cases, high UV exposure |

| Mitomycin C + Excision | 5-10% | 2-4 weeks | Fast-growing or aggressive cases |

| Amniotic Membrane Transplant | 8% | 3-4 weeks | Recurrent pterygium, failed prior surgery |

Autografts are the most widely used because they’re effective, safe, and don’t rely on drugs. Mitomycin C works well but carries a small risk of corneal thinning if overused. Amniotic membrane is newer and excellent for repeat surgeries, but it’s more expensive and not available everywhere.

Prevention: The Real Game-Changer

Here’s the truth: Surgery fixes the problem-but it doesn’t stop it from coming back. The only way to truly win is to prevent it in the first place.

Wear sunglasses that block 99-100% of UVA and UVB rays. Look for the ANSI Z80.3-2020 standard on the label. Wraparound styles are best-they stop UV from sneaking in from the sides. A wide-brimmed hat cuts UV exposure by another 50%.

Don’t wait until you see a growth. Start now. Even if you’re 25 and think you’re fine. UV damage builds silently. One study showed that people who wore UV-blocking sunglasses daily for five years had 50% less progression than those who didn’t.

Also, avoid direct sun between 10 a.m. and 4 p.m., when UV levels peak. Check your local UV index. If it’s above 3, protect your eyes. That’s true even in winter or on cloudy days.

What’s New in Treatment?

The field is evolving. In March 2023, the FDA approved OcuGel Plus-a new preservative-free lubricant designed specifically for post-surgery healing. It reduced discomfort by 32% compared to standard drops.

Researchers are testing topical rapamycin, a drug that blocks the cells responsible for regrowth. Early trials show a 67% drop in recurrence at one year. If approved, it could become a daily eye drop to prevent pterygium from coming back after surgery.

By 2027, most eye surgeons expect to use laser-assisted removal. It’s faster, more precise, and causes less trauma. But it’s not widely available yet.

Who’s at Risk? The Hidden Groups

It’s not just surfers or farmers. Men are 1.5 times more likely to develop it than women-likely because they spend more time in outdoor jobs. Rural populations in developing countries have almost no access to surgery. Only 12% get treated, compared to 89% in urban areas of wealthy nations.

If you’re a construction worker, a fisherman, a gardener, a cyclist, a skier, or even a parent who takes kids to the park every weekend-you’re at risk. It doesn’t matter how dark your skin is. Your eyes are still vulnerable.

What to Do Next

If you’ve noticed a pink or red growth on your eye:

- See an eye doctor. Don’t wait. A slit-lamp exam takes five minutes.

- Start wearing UV-blocking sunglasses daily-even indoors if you sit near a sunny window.

- Get a wide-brimmed hat. It’s cheap and effective.

- If your doctor says it’s early-stage, stick with eye drops and protection. Don’t rush to surgery.

- If it’s growing toward your pupil, ask about conjunctival autograft or mitomycin C. Avoid simple removal.

- Track your UV exposure. Use apps like UVLens or check your local weather service’s UV index.

There’s no magic cure. But there’s a clear path: protect your eyes, get checked, and act early. Pterygium isn’t an emergency. But if you ignore it, it can become one.

Can pterygium cause permanent vision loss?

Yes, but only if it grows large enough to cover the center of your cornea. Most cases don’t reach that point. If caught early and treated, vision loss is preventable. The key is not waiting until your vision is blurry.

Is pterygium surgery painful?

No, the surgery itself isn’t painful-you’re numbed with eye drops. Afterward, you’ll feel grittiness, watering, and mild discomfort for a few days. Most people describe it as a scratchy or burning sensation. Painkillers aren’t usually needed, but steroid drops are essential to reduce swelling and prevent recurrence.

Will my eye look normal after surgery?

Not right away. Your eye will be red and swollen for 2-4 weeks. That’s normal. The redness fades slowly. Most patients say their eye looks natural after 2-3 months. A small scar may remain, but it’s usually barely noticeable. Cosmetic concerns are common early on but improve with time.

Can pterygium come back after surgery?

Yes, in about 10% of cases-even with the best techniques. The biggest risk factor for recurrence? Continuing UV exposure after surgery. If you don’t wear sunglasses and a hat afterward, your chances of regrowth jump dramatically. That’s why prevention doesn’t end at the operating room.

Are over-the-counter eye drops helpful?

They can help with symptoms like dryness and irritation, but they won’t shrink or stop the growth. Artificial tears keep your eye comfortable. Prescription steroid drops may slow growth in early stages, but they’re not a cure. The only way to remove it is surgery.

How often should I get my eyes checked if I have pterygium?

If it’s stable and not affecting vision, once a year is enough. If it’s growing or causing discomfort, see your eye doctor every 6 months. Bring your sunglasses to the appointment-your doctor will want to see what kind you’re using.

Don’t wait for blurry vision to act. Your eyes are exposed every day. Protect them like you protect your skin-from the sun, from the wind, from time. Pterygium isn’t inevitable. It’s preventable. And if it’s already there? You still have control. The right treatment, the right protection, and the right timing can keep your vision clear for decades.

I’ve had a pinguecula for years and never realized it could turn into something worse. I started wearing my sunglasses every day after work-even when it’s cloudy-and I feel like I’ve already won. Thanks for making this so clear.

Also, if you’re on a budget, look for UV-blocking clip-ons for your regular glasses. They’re like $15 and work great.

From a clinical ophthalmology standpoint, the conjunctival autograft remains the gold standard due to its favorable risk-benefit profile in mitigating recurrence via stromal re-epithelialization and suppression of fibrovascular proliferation. Mitomycin C, while efficacious, carries a non-negligible risk of corneal endothelial toxicity, particularly with prolonged exposure or excessive concentration.

Amniotic membrane transplantation, though superior in recurrent cases, is limited by cost and regulatory heterogeneity across jurisdictions. The 92% success rate cited is from a 2023 multicenter European cohort study (n=147) with 12-month follow-up-statistically robust but not universally generalizable.

It is imperative to underscore that ultraviolet radiation exposure constitutes the primary etiological factor in the development of pterygium, as substantiated by longitudinal epidemiological data from the Australian National Eye Health Survey. The cumulative dose-response relationship is unequivocal.

Furthermore, the assertion that ‘sunscreen for your eyes’ is sufficient is misleading; only ANSI Z80.3-2020-compliant wraparound eyewear provides adequate ocular protection. Broad-brimmed hats contribute significantly to reducing ambient UV flux by approximately 50%, as demonstrated by radiometric measurements in controlled field studies.

Okay, so let me get this straight-your eye is basically a sunburn that never heals and slowly creeps toward your pupil like some kind of creepy, pink, fleshy zombie? And we’re just supposed to sit here and let it happen until it’s too late?

And now they’re using PLACENTAL TISSUE from a dead baby to fix it?! I’m not saying it’s wrong, but… WHY IS THIS A THING?!

I’m out. I’m moving to Alaska. And I’m wearing 10 pairs of sunglasses at once.

Let’s be real-this isn’t about the sun. It’s about the government. They’ve been spraying UV-boosting chemicals in the atmosphere since the 90s to keep people distracted with ‘eye problems’ so they don’t notice the real issue: the 5G towers that are frying your optic nerves. And don’t think I haven’t noticed how every single ‘eye doctor’ you see is owned by Big Pharma.

They want you to think sunglasses are the answer-when the real solution is to stop flying, stop using WiFi, and start wearing lead-lined goggles. And don’t even get me started on amniotic membranes-they’re harvesting tissue from unborn babies to cover up the fact that they’re poisoning us all.

Also, why is everyone so obsessed with Australia? Are they running a secret UV experiment? And why are they always the ones with the highest rates? Coincidence? I think not.

Someone’s lying. And it’s not me.

Check the UV index. Check the sky. Check your soul.

Wake up.

They’re watching you.

And your eyes are the first thing they’re taking.

Wow. A 100% accurate, science-backed post that doesn’t scream ‘clickbait.’ I’m almost suspicious.

But seriously-this is the kind of info people need. I’ve seen so many guys in their 50s with massive pterygia who swear they ‘never go outside.’

Then you ask where they sit during lunch. Oh. The patio. With no hat. And their cheap polarized sunglasses that say ‘UV400’ but have no certification.

Y’all need to stop lying to yourselves. Your eyes aren’t invincible. And no, ‘I have dark skin’ doesn’t protect your corneas.

Wear the shades. Buy the hat. Live longer.

Also, Mitomycin C is terrifying but effective. I’ve seen it work. I’ve seen it fail. Don’t skip the follow-up drops. They’re the real MVP.

Think of your eyes like a car windshield. You don’t wait until it’s cracked to put on a sunshade. You do it every day, even when it’s cloudy, because you know the sun’s still out there.

Same deal. You don’t need to be a surfer to get ‘Surfer’s Eye.’ You just need to live outside. And if you’re reading this, you probably are.

Grab a pair of wraparounds. Put ’em on. Don’t overthink it. Your future self will thank you.

And if you’ve already got one? Don’t panic. Just stop feeding it. That’s the real power move.

It is deeply regrettable that Western medicine continues to commodify eye health while ignoring the spiritual degradation of modern society. In India, we have ancient Ayurvedic remedies-such as Triphala eye wash and Surya Namaskar-that have preserved vision for millennia without surgical intervention.

Why do you rely on foreign pharmaceuticals and plastic sunglasses when your own traditions offer purity and balance?

Our ancestors walked under the sun for centuries without pterygium. Why? Because they lived in harmony. You, however, are addicted to screens, air conditioning, and toxic sunglasses imported from America.

Return to the sun with reverence. Not fear.

And stop blaming the UV. Blame your soul’s lack of discipline.

My mom had this and didn’t even know it until her eye started watering all the time. She thought it was allergies. Took her 3 years to go to the doctor.

She got the autograft. Now she wears her sunglasses like a crown. And she’s always telling everyone: ‘It’s not just for the beach, honey.’

Just… wear the damn shades. Even if you think you look silly. Your eyes don’t care how you look. They just want to live.

So let me get this straight-you’re telling me the same sun that gives me vitamin D is slowly turning my eyeballs into a pink swamp?

And I’ve been wearing ‘UV-blocking’ sunglasses that cost $12 from Target?

…I’m not mad. I’m just disappointed.

Also, I live in Cape Town. We get UV levels that’ll make your eyes cry. And half the people I know wear sunglasses like accessories. Like they’re at a fashion show.

Bro. Your eyes are not a runway. They’re your window to the world. Protect them like you’d protect your phone from water. Because once it’s gone… it’s gone.

The sun is a gift from God. To fear it is to fear life itself. Why do we hide from the light? We are made of stardust. Our eyes were made to see the sun.

Perhaps the pterygium is not a disease. Perhaps it is a sign. A sign that we have forgotten how to live. That we have become weak. That we have lost our connection to nature.

Wear sunglasses if you must. But do not fear the sun. Embrace it. Walk barefoot. Let your eyes feel the truth.

Healing comes not from surgery. But from surrender.

It is a matter of profound scientific and ethical concern that the medical establishment continues to promote surgical intervention as the primary solution to a condition that is, in essence, a manifestation of environmental negligence.

Furthermore, the commercialization of amniotic membrane transplantation-while statistically effective-is an ethically dubious practice that commodifies human tissue for profit, while ignoring the root cause: systemic failure in public health education.

Why are we not mandating UV education in schools? Why are we not requiring UV-blocking eyewear in outdoor work permits? Why are we treating symptoms instead of preventing them?

And why does no one question why Australia leads the world in this condition? Is it climate? Or is it cultural complacency?

It is not the sun that is the enemy. It is our indifference.

Okay but have you seen the TikTok trend where people post their pterygium like it’s a trophy? 🤯

‘Look at my Surfer’s Eye!’ ‘I’ve had it for 12 years and it’s still growing!’ ‘My surgeon said it’s ‘artistic’ 😭’

And then they post it with a filter that makes it look like a glowing alien eye and get 200k likes.

Meanwhile, I’m over here wearing polarized Oakleys and a sun hat like a paranoid grandma.

Who’s the real winner here? 🤔

Also, Mitomycin C is basically magic juice. I’d take it. I’d take it with a side of laser and a chaser of amniotic membrane. Just… please don’t make me wear drops for six weeks. I’ll cry. I’ll sob. I’ll write a poem about it.

😭👁️🗨️🫂

They say UV causes it but nobody talks about how blue light from screens is just as bad

And nobody mentions that most sunglasses are fake

And nobody says that if you're not getting enough sleep your eyes can't repair themselves

And nobody tells you that stress makes inflammation worse

And nobody asks why this is happening more now

It's not just the sun

It's everything

And we're all just waiting for someone to fix it with surgery

When we should be fixing our lives